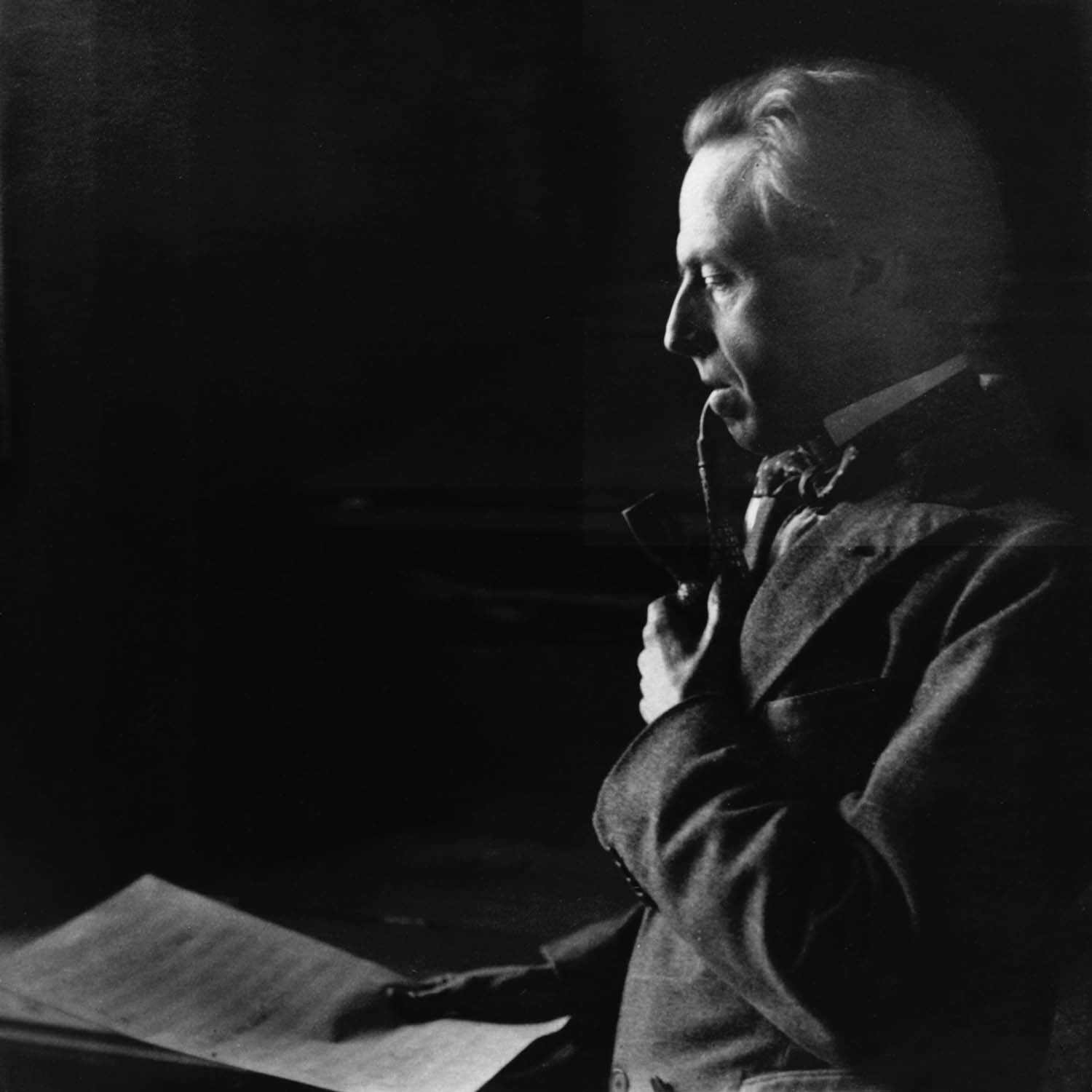

Cyril Scott: Author, Poet and Philosopher

by his son and administrator: Desmond Scott

The Author

In alternative medicine Scott was a pioneer and great advocate years before it became mainstream, writing books with titles like ‘Simpler and Safer Remedies for Grievous Ills’ ‘Doctors Disease & Health’, ‘Constipation and Common sense’ and ‘Victory Over Cancer’. His pamphlets on Black Molasses and Cider Vinegar sold in hundreds of thousands all over the world bought largely by people who were unaware he’d written a note of music!

In the three books he wrote on ethics, ‘Childishness’, (1930) ‘Man Is My Theme’ (1939) and ‘Man, the Unruly Child’ (1953), covering morals, politics, war and religion Scott contended that even after thousands of years of civilization we have still not learned collectively to behave in an adult manner.

"What we condemn in our children", he maintained, "we condone in Nations. Children are taught it’s wrong to lie yet governments tell diplomatic lies, manufacturers tell commercial lies, politicians tell political lies and scientists fabricate the results of their experiments. If a child grabs another child’s toy it is made to return it but if a country invades another country and grabs its land it finds a thousand ways to justify its actions and seldom or never returns what it has seized." Sadly, what he wrote fifty years ago still largely applies today!

The Poet

As a young man studying composition in Frankfurt in the 1890s, Scott met the German poet Stefan George who had a lifelong influence on him. Years later, in 1910, he translateda selection of George’s poems into English titled The Grave of Eros, and dedicated it tohim as ‘The Awakener within me of all Poetry’ He was, for adecade, very productive. His first volume, The Shadows of Silence and the Songs of Yesterday was published around 1905. The Grave of Eros and the Book of Mournful Melodies, with Dreams from the East in 1907, The Voice of the Ancient in 1910, and The Vales of Unity in 1912. He’d also translated Charles Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil in 1909. His last book of the decade, The Celestial Aftermath, was published in 1915. None of these books is still in print. Scott’s verse is intensely romantic, one of his favourite poets being Ernest Dowson (1867-1900), many of whose poems he set to music. What he said of Dowson could apply equally well to his own verse: “Although passion is not missing from some of Dowson’s lyrics, it is always enshrouded in an atmosphere of roses and violets, of softness and shadows”.

After a gap of twenty-five years, during which time he had been busy composing music and writing books he produced in 1943, his final volume, The Poems of a Musician. It is a collection of what he considered his best verses culled from the earlier volumes, some revised for this new edition, and also a number of entirely new ones. It contains not only some of his finest lyrical work but also expresses in verse the philosophy and beliefs he held so dearly. It has never been published.

As an example of his lyrical poetry, here is the second and final stanza of ‘Invocation’, revised from the original of 1910:

Now the summer suns have set for thee,

Faded visions softly rise to sink in me;

Oh let thy radiance bathe me ere the plains be oversnowed,

And Summer’s leaves lie dead upon the road.

Autumn love, turn not thy face from me,

Let thy gentle spirit sing again through me!

Thy scentless asters shall replace the rose and fragrant nard

And robin’s chirp the throstle’s rich aubade.

Introduction

Cyril Scott told his early biographer, Alan Eaglefield Hull in 1918 that:

‘he felt that were he not a musician he could not be a poet, and were he not a poet he would compose a very different sort of music.’

For a decade he had been prolific poetically, publishing The Shadows of Silence and the Songs of Yesterday around 1905. The Grave of Eros and the Book of Mournful Melodies, with Dreams from the East in 1907, The Voice of the Ancient in 1910, and The Vales of Unity in 1912. He’d also translated Charles Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil in 1909 and a selection of poems by Stefan George in 1910. The Grave of Eros is dedicated to George. ‘The Awakener within me of all Poetry’.

His last book of the decade, The Celestial Aftermath, was published in 1915 during WW1.

During WWII, after an interval of more than twenty-five years and under very different circumstances, he turned again to writing poetry. 1915 found Scott in the forefront of British composers and admired by men as diverse as Debussy, Elgar and Stravinsky. Between 1903 and 1914 he had written more works for the piano than any other composer with the exception of Scriabin. His reputation both in Britain and in Europe was at its highest. 1942 by contrast was one of the lowest points of his life. He had left his London home when war broke out and was living in various lodgings in the West of England. He was depressed, unwell, in hospital for a short time and at 63 wrote to his great friend the Australian composer Percy Grainger that he felt death to be near. He was worried about money and in unfamiliar surroundings without a piano felt unable to compose.

Fortunately, as he wrote in his second autobiography, Bone of Contention (1969):

“Holding the belief that the more subjects one can, within limits, become interested in, the less time and inclination one has to be unhappy, I will make no excuses for what the friends of my music call my versatility and its detractors the dissipation of my energies, for… in a sad plight is the composer who has no side line or pastime to turn to during those desolate periods when musical ideation gives out, leaving but that painful sense of emptiness and frustration so familiar to all creative artists.”

Scott’s sidelines included publishing thirty-three books, not only on music but on a wide variety of other topics. There was also painting, playwriting, and poetry. Poetry appealed to him particularly. It was a relaxation from and less arduous than composing and enabled him to express his ideas and his philosophy in more concrete terms than in his music. The sound, the spoken music of the poetry, was as important to him as the meaning. His vocabulary is elaborate, ornate and exotic. Stylistically it is late Victorian but in thought it has more in common with the Mystical 17th Century poets Henry Vaughan and Thomas Traherne who saw beyond any creed or religion to the unity of all things and were inspired, as was Scott, by a spiritual concept of the world that informed every line they wrote.

The Poems of a Musician completed in September 1943 is divided into sections. The first, titled Nature Lyrics and Songs of the Heart contains fifteen poems, many of them revisions of earlier pieces, including some better known ones such as The Garden of Soul-Sympathy, Poppies, The Twilight of the Year, here called Autumn Mood, and Bells. The new poems are beautifully evocative expressions of mood or of the seasons. In Invocation, to a lost love, he writes:

Oh let thy radiance bathe me ere the plains be oversnowed, And summer’s leaves lie dead upon the road.

which captures perfectly the feeling of longing and of melancholy. Two poems, Villanelle of Spring and Villanelle of Autumn, though occasionally straining for rhyme, are written very successfully in that intricate verse form and his fondness for exotic words such as ‘morient’, which means dying, serves to create an intensely romantic otherworldly atmosphere.

Occasionally his love for the sound of a word misled him as when in an earlier version of Bells he wrote: ‘bells across the lone lassitude’. Lassitude is a splendid word and one can see why he chose it but it is a state of mind or body, so in this context makes little sense. Perhaps someone pointed that out to him because here he’s changed it to: ‘Bells across the vast solitudes’. Not everyone approved of the change. Percy Grainger in 1947 complained:

'Cyril has allowed himself to be drawn out of a vague,

eerie EMOTIONAL landscape into a reasoning, concrete GEOGRAPHICAL landscape.’

and much preferred the original.

The next section Through other Eyes is radically different. The language is simpler and more direct. The three poems, each called Lamentation are all concerned with the war, which in 1942 and early 1943 was going badly, the tide yet to turn in favour of the Allies.

In the first poem the parents of a dead soldier lament the loss of their only child.

The piece by which as a composer Scott is best known is undoubtedly Lotusland (1905). It has been recorded over fifty times both in its original form for piano and in a wide variety of arrangements from vocals to jazz groups and from brass bands to synthesizer. Later he also wrote a poem with the same name. The thought and language carry us back to Tennyson’s ‘The Lady of Shalott’ or Rossetti’s ‘The Blessed Damozel’ but the atmosphere is entirely Scott’s own, sensuous, dreamy and otherworldly.

Lotusland

Illumed by radiance of resplendent dawns,

That flood the dazzling dome of an Eastern strand;

The Lotus-Lady mourns!

Lost in the dreamy realms of Lotusland.

Afar she looks across her lotus lawns,

By mortal step or mortal eye unscanned;

The Lotus-Lady mourns!

Kissed by the spectres lost in Lotusland.

A zone of gems her fragrant brow adorns,

By seven mystic maids her face is fanned

The Lotus-Lady mourns!

For her lover fled from Lotusland.

Around the same time (1912) Scott composed a suite of five short piano pieces he called Poems with titles such as ‘Bells’, ‘The Garden of Soul-Sympathy’ and ‘Paradise Birds’. Again he wrote verses with the same titles. Both poems and music are complete in themselves but here Scott’s thought was to have them performed together, the combination creating an experience more deeply felt and intense than either on its own.

There are many recordings of the Poems and often the liner notes provide the text of the verses but so far none has put together voice and piano as Scott intended. In the public lectures I have given, Corinne Langston has recited the verses while various musicians have played the work and the result has been all that Scott hoped for!

The Philosopher

Reacting against what he regarded as the narrow piety of his Victorian parents Scott briefly turned agnostic, then became interested in Theosophy and finally in Occultism which he described as a synthesis of Science, Philosophy and Religion. It influenced his life profoundly. In two books, ‘An Outline of modern Occultism’ (1935) and his second autobiography ‘Bone of Contention’, (1969) published a year before his death, he set down the following principles of Occultism.

That from the Occult viewpoint the basic truths of all the great religions are the same, differing only in their outer manifestations.

That there is no such thing as the supernatural, but only the supernormal;

That Spirit is Matter in its rarest aspect and Matter is Spirit in its varying degrees grossest form.

That Occultism embraces Karma (the law of cause and effect) and Reincarnation.

That there is a Hierarchy of those who, after many incarnations have evolved more than the great majority of humanity.

These Initiates, Sages, or Masters seek to further the spiritual evolution of all humanity by inspiring the best in philosophical, religious, scientific, ideological and artistic trends. But as Man has a measure of free will they always seek to guide and never to coerce.

In 1920 he wrote the first volume of an extremely popular trilogy concerning one such Initiate, simply titled The Initiate. The second and third volumes, The Initiate in the New World and The Initiate in the Dark Cycle followed in 1927 and 1932. They remain in print today, are still being translated into different languages, and have been optioned for a film.

Another book, again largely governed by his Occult beliefs was Music, Its Secret Influence Throughout the Ages. In it he states that certain composers throughout history have been inspired by Initiates and by one in particular, Master K.H. This is a thought-provoking and intriguing book which despite, or perhaps because of, its controversial thesis was also very popular. First published in 1933, it remained in print for over fifty years reprinted in both hard cover and paperback editions. Beethoven said music could change the world. Scott agreed but in his book goes further and maintains it influences the world in much more profound ways than we imagine.

The arts are usually regarded as a reflection of the culture of their time; Scott on the contrary declared art, particularly music, influenced and even created the culture that followed it. The music of Handel, he maintained, revolutionized English morals, causing the pendulum to swing from extreme laxity during the Georgian era to undue restraint during the Victorian. The music of Bach with the mathematical ingenuity of his fugue writing led to greater intellectual activity while the music of Beethoven led later on to psycho-analysis!

Scott’s beliefs are important for an understanding both of the man and his work. He felt guided, sustained and comforted by his Master in the same way adherents of other faiths feel guided and sustained. Toward the end of World War II when it seemed to him that musically he had nothing left to say his Master urged him to continue and he obeyed, composing, among many other works, a large Hymn of Unity (1947). This Oratorio, for which he also wrote the libretto, embodies all he stood for and believed in. He wrote it fully aware he was most unlikely ever to hear a performance of it during his lifetime but he continued straight on writing and composing, happy when some of his music was played and happier still when he received letters from people who told him they had benefited from his books.

As Sir Thomas Armstrong, who was Principal of the Royal Academy of Music and President of the Cyril Scott Society (now no longer in existence) said in a BBC radio broadcast in 1977 "Cyril Scott was a marvellous example of the dedicated creative artist".